| « Previous | All topics | Next » |

Over There: Arriving in EuropeAn Independent Army and a Race Against Time

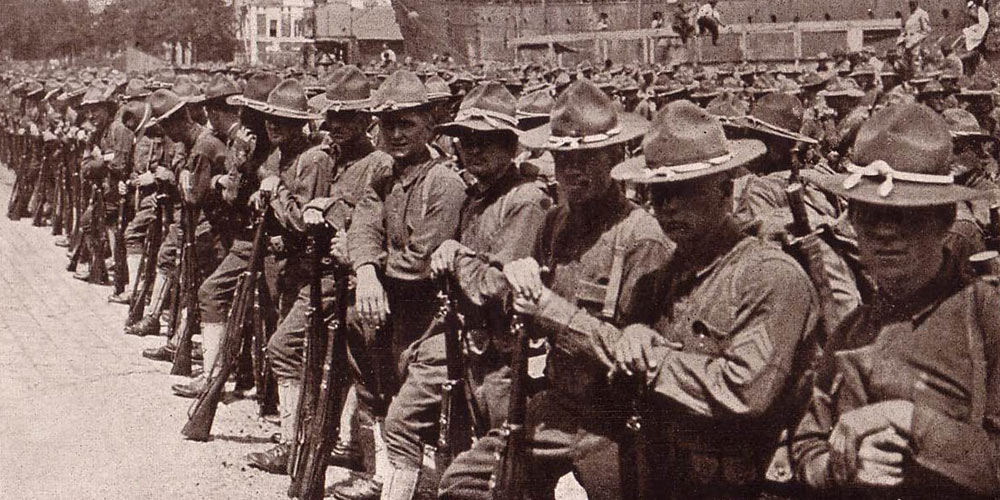

The AEF was commanded by General John “Black Jack” Pershing, a veteran of the Spanish-American War and commander of a 1916 raid to hunt Mexican guerilla leader Pancho Villa. On July 4, Pershing led a parade of U.S. troops through cheering crowds in the streets of Paris. The Americans marched to the tomb of the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the Revolutionary War, where they declared that the U.S. had come to repay its old debt to France.

An Independent Army

Pershing and his staff began preparing the AEF for battle. In earlier negotiations, the British and French had pressed to use American troops to fill in their depleted ranks. President Woodrow Wilson and Pershing refused, insisting on organizing the AEF as an independent force under American command.

The Americans were assigned to the area around Lorraine, in the east of the Allied lines. Pershing’s staff set up camps to house the troops, training programs to prepare them for combat, and communications and supply networks.

American industry had just begun to shift to full wartime production, so U.S. units were mostly supplied with Allied equipment, especially tanks and airplanes. American troops learned Allied trench combat techniques, but Pershing insisted on additional training in marksmanship and maneuver warfare, as he intended to get the Germans out of their positions and into the open.

At first, the arrival of eager, fresh Americans provided a much-needed morale boost to the exhausted Allies. However, this early optimism faded a bit when it became clear that the new arrivals were not ready to fight. Many British and French troops became resentful of the well-fed and well-paid doughboys, who had yet to prove themselves under fire. America’s fighting men would have to earn respect in combat, not just from the enemy, but from their allies.

On October 21, 1917, units from the U.S. Army’s First Division entered the front lines near Nancy, France. Two days later, Robert Bralet became the first U.S. soldier to fire a shot in the war when he discharged a French 75mm gun at the German lines. On the night of November 2, James Gresham, Thomas Enright and Merle Hay became the first U.S. soldiers to die in combat when Germans raided their trenches near Bathelemont, France.

Through the end of 1917 and into 1918, the AEF continued to grow and train. Pershing planned to spend 1918 building up an overwhelming force and then to attack and win the war in 1919. However, the Germans had other plans.

A Race against Time

Germany had resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 knowing it would likely provoke the U.S. to enter the war. However, it believed that it could defeat the Allies before enough Americans arrived to make a difference. After Russia’s departure from the war and Austrian/German victories on the Italian front, Germany began moving men to the Western Front for its own effort to win the war.

| « Over There: Arriving in Europe | All topics | Defeating the U-Boats: The U.S. Navy » |

Lessons/resources

Search the National WWI Museum & Memorial Resource Database

More resources/lessons

» The Harlem Hellfighters: Remembering the 369th Infantry Regiment

Study guide (includes link to 7 min video) with summaries and suggested discussions/activities. | HISTORY

» Artists Document World War I

Online activity and discussion, built around artwork of U.S. troops arriving in France. | National Archives

» U.S. Army Center of Military History: General Resources | World War I

Official publications and records about the U.S. Army in World War One. | U.S. Army Center of Military History