| « Previous | All topics | Next » |

The HomefrontMobilizing America's Economy and Society

After a slow start, the U.S. government implemented measures aimed at improving efficiency and mobilizing public involvement. Some of these efforts were controversial, but for the most part, they were successful The government’s role in World War I set a precedent for its increased involvement in America’s economy and society in general.

Propaganda

In the first months after the U.S. entered the war, many Americans still did not fully support the decision to join the conflict. President Woodrow Wilson created the Committee on Public Information to encourage the American people to support the war effort. The Committee produced articles, posters, pamphlets, movies, speeches and rallies that promoted the Allied cause and painted the Central Powers (especially Germany) as enemies of democracy and civilization. In addition, Congress passed two laws of questionable constitutionality. The Espionage Act gave the government broad powers to inspect communications by mail. The Sedition Act made it illegal to even speak against the war effort or the U.S. Government. Both laws were challenged in court; at the time, both were upheld by the Supreme Court as necessary for the war. These measures fueled strong anti-German sentiment. German-Americans faced harassment and abuse; many changed their names to more English-sounding versions. In the hysteria, sauerkraut was renamed “liberty cabbage”, dachshunds were called “liberty pups” and even German measles became “liberty measles.”

Conservation measures

To free up resources for the military and for America’s European allies, the government promoted conservation. The Food Administration was led by Herbert Hoover, who had organized relief efforts for Belgium. The agency promoted voluntary measures, such as meatless Mondays and wheatless Wednesdays. It offered canning lessons and modified recipes, and encouraged Americans to plant vegetable gardens in yards and vacant spaces. These measures helped double the amount of food shipped to Europe within a year and reduced U.S. consumption by 15 percent. The Fuel Administration adopted similar efforts, such as heatless Mondays and gasless Sundays.

Paying for the War

The United States would spend over $30 billion on fighting World War I. In 1913, the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had established a personal income tax. Wartime increases in tax rates significantly boosted funds collected by the government.

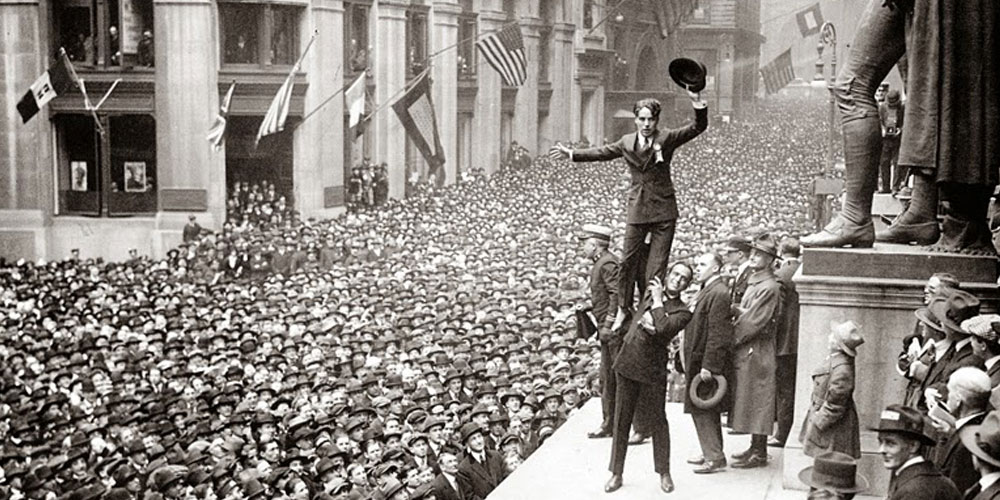

However, most of America’s wartime spending was funded by war bonds. Like savings bonds, war bonds provided purchasers with a guaranteed return at a future date. The government promoted its “Liberty Bonds” with a nationwide campaign calling on the public’s patriotism. It organized huge rallies with famous actors such as Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks and commissioned promotional posters by famous artists. Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts helped sell bonds; Americans from all walks of life purchased them. War bonds would raise over $20 billion for the U.S. war effort.

Wartime Production

From 1914 to early 1917, America supplied war goods to Europe (predominantly the Allies, due to the British naval blockade). However, when the U.S. entered the war, it faced challenges in ramping up to full wartime production. The military and private industry did not work together to prioritize manufacturing needs, and the transportation of resources and products was completely disorganized.

President Wilson created the War Industries Board to set production standards and coordinate railroad and shipping efforts. The National War Labor Board secured the cooperation of American workers by setting higher wages and an eight hour workday, and recognized the right to unionize. Many jobs were left vacant by men called into military service; women stepped in to fill the gaps.

Although these measures helped make America’s war effort more efficient, the war ended before they could make a major impact on its actual output. However, they set a precedent that influenced the government’s role in the economy a generation later, during the New Deal and World War II.

Service and sacrifice

Service flags were hung in the windows of homes across America, decorated with a blue star for each family member in the military. If a family member lost their life, the blue star was covered with a gold one.

Blue and Gold Star service flags were widespread during both World Wars, but fell out of use until they were revived by post-9/11 military families.

| « The Homefront | All topics | Birth of an Army: Spring 1918 » |

Featured links:

The Star Spangled Banner and World War One

How the 1918 World Series played a part in the adoption of our national anthem. | U.S. World War One Centennial Commission

Lessons/resources

Search the National WWI Museum & Memorial Resource Database

More resources/lessons

» Sedition in World War I

Lesson examining free speech issues during the War. | Stanford History Education Group

» Analyze a Poster

Poster analysis worksheet; useful for lessons on propaganda or homefront war effort posters. | National Archives

» Baseball on the World War I Homefront

Online interactive lesson and discussion. | National Archives

» Americans on the Homefront Helped Win World War I

Online lesson based on document exploration and analysis. | National Archives

» Library of Congress: World War I

Homepage for the Library of Congress' extensive WWI collections and resources. | Library of Congress